When utopia is oblivion / Quand l'utopie force l'oubli

An immersive keynote for the iX Symposium / MUTEK Forum

360 interactive video recording of When utopia is oblivion / Quand l'utopie force l'oubli

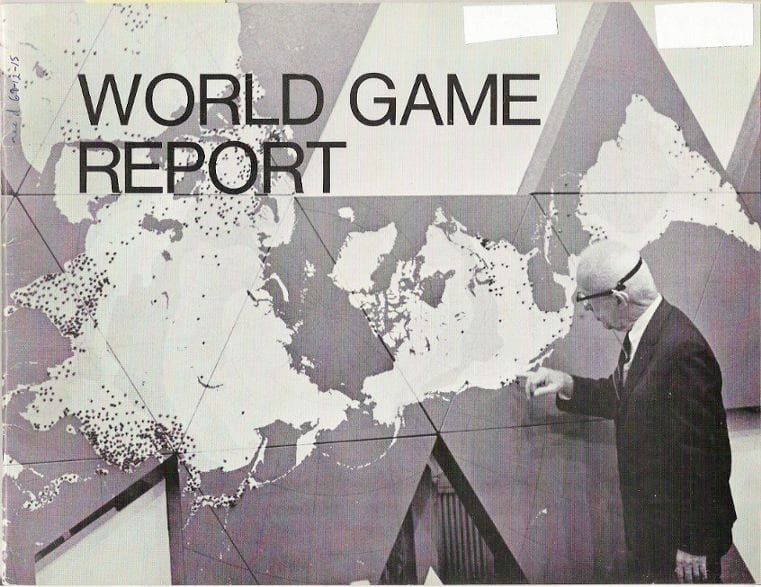

The provocative 1969 book "Utopia or Oblivion" by R. Buckminster Fuller presented a stark choice between binary opposites. But what if they’re deeply entangled? Dreams of utopia (“no place”) frequently require oblivion (”the state of forgetting”) when pursuits of an ideal society are contingent on the erasure of existing realities.

Yet, as the saying goes, the land doesn’t forget — and water has memory. Experience is held in both bodies and places.

This immersive performance examines the consequences of utopian endeavors, from the religious and colonial to the technological and corporate. By uncovering the paradoxes hidden within these idealistic pursuits, we explore the potential of emerging technologies to foster reconnection and remembrance rather than impose exclusion and control — and to fundamentally re-establish relationships with the living world.

I. Exposition

Modern Montréal stands as one of the few cities so directly and recently shaped by a utopian vision. This transformation can be traced back over 60 years ago to the origins of Expo 67, also known as the 1967 International and Universal Exposition. Around that time, Québec was a largely rural province governed by conservative Catholic values, and it underwent a radical shift led by artists and intellectuals that became known as the Quiet Revolution. Some of them saw the international gathering of Expo 67 as Montréal's opportunity to debut on the world stage, showcasing its secular and metropolitan evolution.

The exposition featured numerous provocative exhibits vying for its centerpiece, representing Canada, First Nations, and many other countries around them. They were designed to unfurl the metaphorical plumage of different nations and cultures, each vying for attention. The United States Pavilion, now known as the Biosphere, emerged as one of Expo 67's most iconic structures. While the geodesic dome is well known as a symbol of Montréal, its original proposed purpose was nearly the opposite of what the U.S. pavilion became.

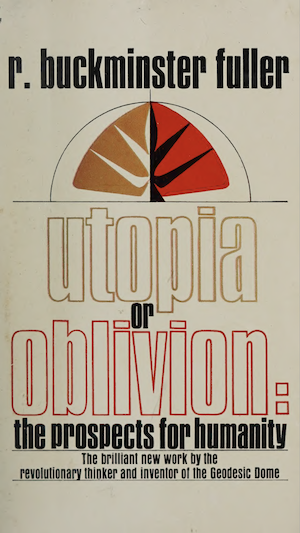

Buckminster Fuller, the American architect and polymath who designed the pavilion, originally envisioned it as a collaborative space where attendees could simulate potential global futures and what he called the World Game. At the height of the Cold War, Fuller imagined the pavilion as both a symbol and a physical space for simulating strategies to reconcile global tensions at the time. He originally conceived of it as what he called the World Resources Simulation Center, a place where global citizens could come together to model ways of making the world work for 100% of humanity. For the exterior, Fuller imagined the largest version of what he called his Geoscope, a massive illuminated sphere that would visualize the metabolic flows of what he called Spaceship Earth.

However, the US government rejected all these ideas as being too ambitious, citing both prohibitive costs and limitations of computing and display technologies at the time. Fuller later articulated his pragmatic vision in his 1969 book of essays, Utopia or Oblivion, which described the foundation of his dream. He critiqued previous utopian schemes as being overly exclusive, insisting that a true utopia would be a world that works for everyone.

To address the multiple existential crises facing humanity, Fuller called for a "design science revolution," advocating for the use of technology and comprehensive design. His mantra was to "do more and more with less and less until we can do everything with nothing." Through decades of research and experimentation, he calculated how efficient management of planetary resources could create a world benefiting all of humanity.

Yet, like so many other utopian pursuits, Fuller's quest was riddled with paradoxes and setbacks. The fair itself was housed on constructed islands in the St. Lawrence River, which represented a kind of utopian microcosm for a city stepping into the future. One of the islands was named after Saint Helena, the Roman empress that was also the mother of Constantine the Great, and Constantine was instrumental in bringing Christianity to Rome and making it the official religion of the Roman Empire. The name is a bit ironic, considering Expo 67's role in the secularization of Montréal.

Regardless, Fuller's grand vision was never realized. Instead, the pavilion became a symbol of American power, showcasing its cultural and political propaganda throughout Expo 67, which at the time was kind of at its peak. And then nearly a decade later, during structural renovation, a worker's torch ignited the acrylic shell, creating its own apocalyptic unveiling—though leaving the geodesic structure intact.

II. Utopias

Montréal's Expo 67 echoed an ancient pattern of spheres and islands embodying utopian ideals. They've served as powerful metaphors for imagined perfect worlds—from the heavens and the afterlife to promised lands, lost worlds, and golden ages. They represent dreams of hidden islands or faraway kingdoms, offering an escape from life's complexities, isolated within absolute elsewheres.

Throughout history, cultures have turned to the dome of the sky to make sense of the overarching context of existence. Our ancestors imagined creation stories to explain the world's origins. They charted correlations between celestial movements and life cycles. And these patterns intertwine with human lives, weaving together heavenly and Earthly rhythms. Recognizing this intimate connection between sky and Earth and the cycles of life suggests an order, a structure, a law of existence—which different cultures, of course, each interpret in vastly different ways.

Recognizing this intimate connection between sky and Earth and the cycles of life suggests an order, a structure, a law of existence.

We perceive the heavens as a sphere because our visual field is spherical. The sun, moon, and stars seem to orbit us, which creates the illusion of floating on a vast, infinite sea. Through direct experience, each of us can grasp what it means to be inside or outside, contained or separated. To paraphrase Peter Sloterdijk, the sphere functions as a kind of protective structure and immune system—shielding while nourishing, providing an archetypal form in which to dwell and construct meaning.

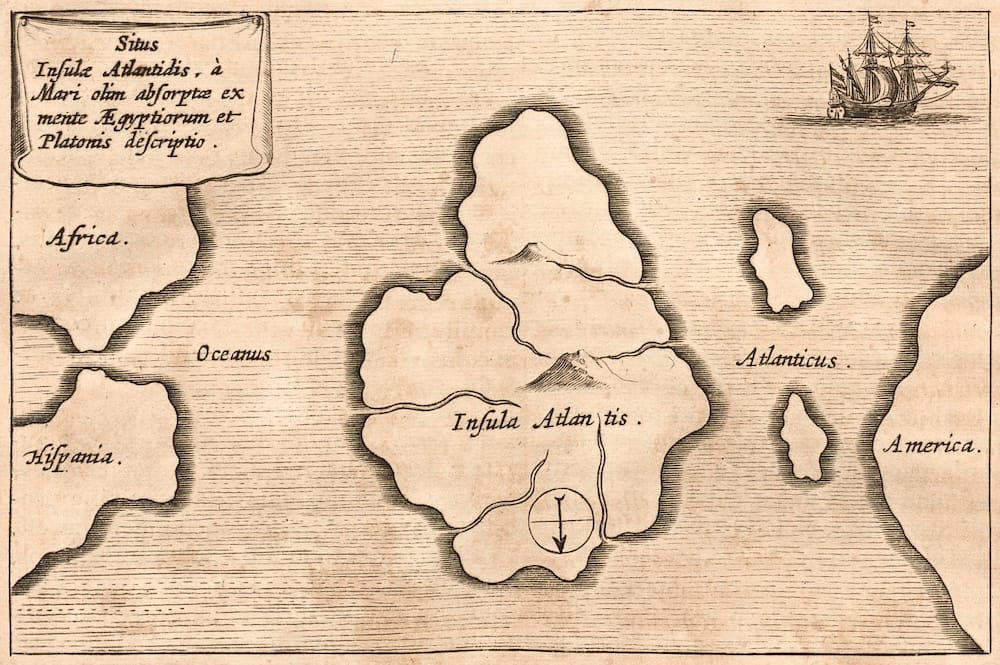

The island utopia has been a recurring trope in literature for centuries, exploring different facets of ideal societies. Plato's Atlantis stands as a cautionary tale. Set 9000 years before Plato's time, it warned of the moral and spiritual decline that can plague an advanced civilization. Initially, Atlantis is defined by remarkable achievements, abundant resources, and just governance. Its founders, claiming descent from the god Poseidon, embodied an ideal of technological domination.

However, they eventually succumb to moral corruption and hubris. Catastrophic earthquakes and floods seal the island's fate. Despite its moral and spiritual foundation, an advanced society with a formidable naval force could not withstand the lure of greed, corruption, and extraction.

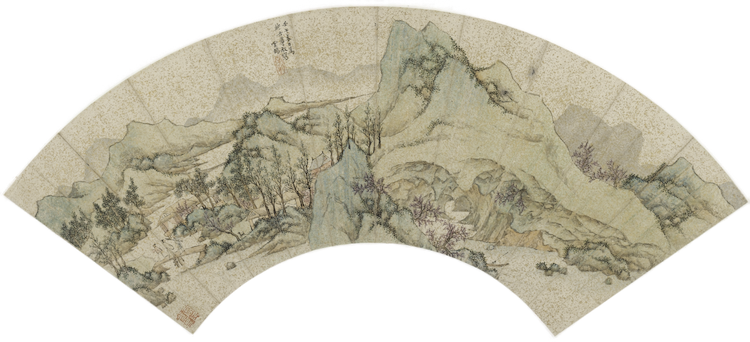

By contrast, some utopias like Tao Yuanming's The Peach Blossom Spring paint pictures of societies living in isolated harmony with nature, embracing equality and communal living.

That story begins with a fisherman who wanders into a peach orchard, and as he goes deeper, discovers a hidden cave. Passing through the cave, he finds himself in a secluded village. It's a sanctuary created by people who, centuries before, had fled a tyrannical political regime. Welcomed and nourished by this serene community, the fisherman is struck by the peace and simplicity of their lives. Before leaving, he promises to keep their existence a secret. But he lies. And upon his return home, he betrays the secret and discovers that he—and no one else—could ever find the Peach Blossom Village again.

The word utopia, meaning "no place," "no where," was coined 500 years ago by Renaissance humanist Saint Thomas More. It was codified in the Western mind and literature as an idealized paradise, characterized by abundance and simplicity. Utopia was the name he gave to an imaginary country on a fictional island. In the "no place" of Utopia, even its river meant "no water."

It described an ideal society defined by communal property, religious tolerance, and an elected government. More wrote Utopia in his late 30s as a man of integrity, who was later executed by the tyrant Henry VIII because he refused to support the king's philandering. While More's utopia is well known, what's lesser known is where he drew inspiration for it.

Around that time, for 400 years, barons and feudal lords had been transforming England's commons into private properties, imposing a proto-capitalist system of land theft and ownership. This enclosure movement had defined how England had been run for centuries, at a time when European colonization was just beginning.

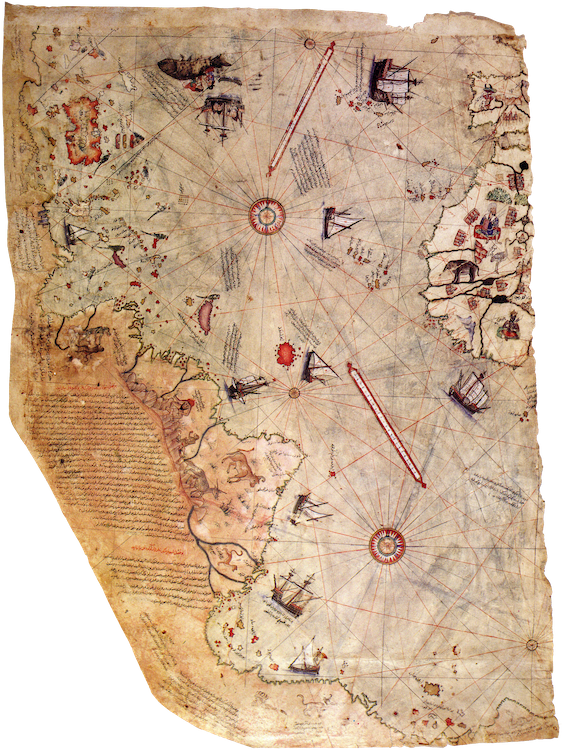

Reports from European explorers were just coming in, with careful drawings and new maps. Thomas More had read the letters of Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci, who had written about Indigenous communities in what he called the "New World." Vespucci's writings were filled with wonder and admiration. He described a land of beauty and plenty, an Eden filled with gold and gardens and other resources to be carried away.

He both idealized and exoticized the diverse cultures he encountered in a land known by many names. One was Abya Yala, meaning "living land" or "land that flourishes." Today it is known as Brazil. And eventually, the entire continent, along with its northern neighbor Turtle Island, was baptized by the Europeans as America, named after Amerigo Vespucci himself.

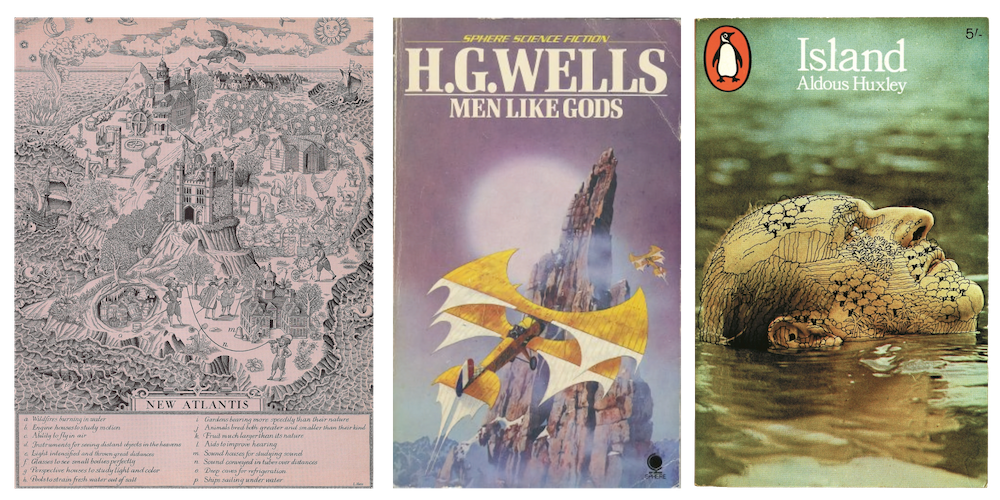

From More onward, this utopian tradition has permeated Western literature ever since. Across a kind of literary archipelago, recurring themes emerge: isolation, harmony, abundance, knowledge, and freedom. Some envision a life free from labor and want, exemplified by the drunken abundance in the medieval Land of Cockaigne. Others, like Francis Bacon's New Atlantis, focus on progress through the pursuit of knowledge, portraying humanity's mastery over nature.

Some depict absolute personal freedom from centralized authority, such as the self-governance in H.G. Wells' Men Like Gods. And others, like Aldous Huxley's Island, explore personal growth and enlightenment by integrating Western science with Eastern spirituality. Each of these fictional utopias, in its unique way, continues to profoundly shape modern visions of idealized societies.

III. Oblivions

Efforts to bring fictionalized utopias into reality are riddled with paradoxes. There's an elusive dance between the literary and the literal. In reality, attempts to create idealized societies often lead to the erasure of existing ones. Consider the real estate developments that are often named after the forests cut to build them. We happen to live in Oakland, which used to have many more oak groves.

The quest for "no place" often requires oblivion, the "act of forgetting or erasing what already exists."

The quest for "no place" often requires oblivion, the "act of forgetting or erasing what already exists." Ironically, it was Vespucci's tales from what he called the New World that fueled More's belief in Eden As Utopia, and that it was within reach. Nearly every aspect of Utopia described by More could be found within the diverse places and practices tended by Indigenous cultures worldwide. Understanding this contradiction, this paradox, this hypocrisy, is crucial to grasping why utopia and oblivion are so often inseparable.

In the Western imagination, the biblical Garden of Eden stands as a quintessential utopia. It represents a perfect unity with God, characterized by immortality and effortless abundance. This idyllic state, however, was lost through the fall from grace, ushering in the suffering and imperfection of our corruptible world.

The notion of falling from an idyllic Eden due to original sin, which separates humanity from God, is unique to Judaism and Christianity. This stands in stark contrast to most non-Western traditions, where utopian ideals are seen as achievable through human effort rather than through divine salvation or the coming of a messiah.

This impulse to transcend Earthly existence lies at the heart of this cosmology, this cosmovision.

This impulse to transcend Earthly existence lies at the heart of this cosmology, this cosmovision. It seeks to constantly step outside of this corruptible world in search of a better one, to hold it in one's hand, to obtain a god's eye view, and to, like God, control it from above. From this flows the imperial justification for power and domination.

Saint Helena's son Emperor Constantine the Great imposed Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire. He promised Utopia in the eternal Kingdom of Heaven if its subjects would submit to his authority on this Earthly one. So for a thousand years, the Roman Church fought to erode the local beliefs, customs, and lives of Indigenous peoples—the Picts, the Celts, the Gauls, and countless others—in the lands that would become known as Europe.

This practice set the stage for European empires to shape entire continents to serve their interests. These colonial powers transformed diverse ecosystems into profitable monocultures, disrupting ecologies and the centuries-old knowledge systems and ways of life that sustained them.

This was sanctioned by the Roman Church under the auspices of the "divine right of kings," based on the legal and moral authority of the hierarchy of the so-called "great chain of being." In this, God as a King sits at the top. And down through the chain, you see the angels and the humans and the animals and the plants and the rocks, and eventually, at the very bottom, you see Hell, with the Devil at the center—who was a woman, of course. And in this universe, the king sits above all else.

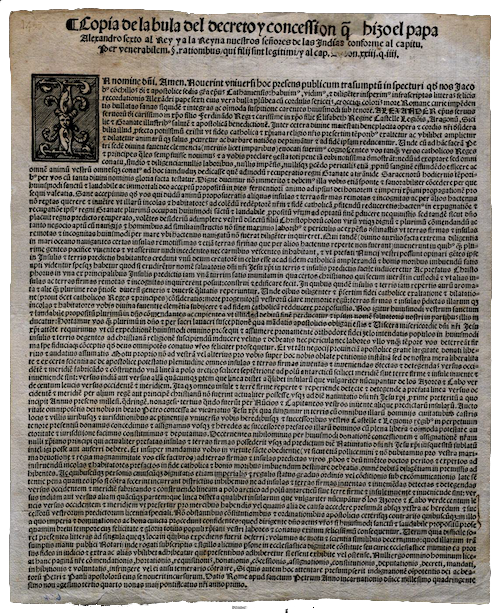

Beginning in the 15th century, the popes issued a series of edicts called papal bulls, collectively known as the doctrine of discovery, that commanded European monarchs to "invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue" non-Christians. This doctrine was used to legally justify the conquest of the so-called "New World" for resource extraction and slavery to enrich the colonial empires. It repurposed the Roman concept of terra nullius, which means "no man's land," to claim that Indigenous inhabitants couldn't own their native lands. And, believe it or not, this is still used as legal precedent in both American and Canadian law today.

Utopias continue to be used as the ends to justify any means, often in the name of "progress" and "enlightenment."

To this day, aspiring empire builders continue to pursue their own utopias by reshaping existing cultures and landscapes. They often attempt to erase Indigenous realities, the very foundations upon which Thomas More's original vision of Utopia was based. In essence, the pursuit of Utopia frequently demands a form of collective amnesia, erasing the complexities and imperfections of real human societies in favor of abstract ideals. This tension between aspiration and erasure lies at the heart of these endeavors, reminding us that fantasies of perfection often exact a steep price. Utopias continue to be used as the ends to justify any means, often in the name of "progress" and "enlightenment."

In the United States, the "divine right" extended through the concept of "manifest destiny." It was seen as a mandate to expand across the continent, used to rationalize the genocide and displacement of First Nations. And later the Third Reich cited the success of American expansion as a primary inspiration for their own territorial ambitions.

From Armageddon to the Messiah, from the Second Coming to the Third Reich, from the Promised Land to the Singularity, utopian pursuits too often promise salvation and liberation for some while creating oblivion for countless others. And today, new utopias beckon, powered by the promise of technological salvation.

To find out what this looks like, I asked ChatGPT to create its own version of techno-utopia. So the images you're going to see behind me are just a series of synthesized images, and I kept asking it to, like, "Make it more utopian. No, more utopian. More utopian!" If you want an example of how abstract it can be, watch what it does.

Investors and enthusiasts herald an era of unprecedented potential, hyping novel currencies, parallel worlds, and synthetic intelligences. All promise hot returns while casually monetizing every aspect of human existence. And like the philosopher kings of Plato's Republic or the scientists of Bacon's New Atlantis, today's hype men cast themselves as the enlightened few destined to guide humanity toward a prosperous and boundless future.

Yet such dreams of technological salvation are often predicated on the very forces devouring the web of life. Moving fast and breaking things requires voraciously consuming water, energy, minerals, labor, and capital—all with the insatiable appetite of a hungry ghost. And a sleight of hand occurs.

Moving fast and breaking things requires voraciously consuming water, energy, minerals, labor, and capital—all with the insatiable appetite of a hungry ghost.

It obscures utopia's long shadow, the well-worn oblivions of erasure, appropriation, and neo-feudalism. Unlike Fuller, today's techno-optimists promise digital transcendence by ignoring the dynamics of planetary metabolism and local ecologies. Meanwhile, personal escape fantasies—from hedonistic libertarian enclaves on the playa to fortified bunkers to off-world colonies—betray an underlying desire to construct isolated utopias, free from the Earthly constraints of law, ecology, and morality.

And who can blame them? These constraints are tedious and complex. So instead, utopian ventures are often wrapped in the language of altruism and claimed to be vital for the long-term survival of humanity. Curiously, and I find this rather remarkable, these enthusiastic defenders of Western civilization seem to have skipped over the lesson of Plato's Atlantis, in which a technologically advanced society collapses under the weight of its own hubris.

IV. California

These days, we live in a place where so many of these dreams are cultivated. I'm from eastern Ontario, and David is from southern Appalachia. We never expected to live in urban California. And living in a mythologized place is strange. We flicker between the reality of circumstance and the cultural imaginary projected onto it—its peoples and weathers and cultures.

California was first represented on European maps as an island, slicing off the long Baja Peninsula in what's now northwestern Mexico. This famous cartographic error was copied over a thousand times, and the idea of the island of California persisted for centuries. Just a little earlier, in 1500s Spain, there was a popular utopian romance novel about an island civilization inhabited entirely by powerful Black women warriors and ruled by Queen Califia. In the novel, that island was named California. And so when Spanish explorers under the infamous Hernan Cortez encountered the Baja Peninsula, they named it California after the fictional utopia, an early example of how the place was used by European migrants as a canvas of utopian ideals.

Colonizers projected all kinds of wild ideas onto the place, including European ecological notions of how rivers should flow, how food should be grown, and how forests should be tended — or not tended. These utopian visions were then etched on the landscape, written on the land and through the waters.

These utopian visions were then etched on the landscape, written on the land and through the waters.

We found ourselves in Huchiun, the land of the Chechenyo-speaking Ohlone people, also known as Oakland, California, in a kind of beautiful fall-out of utopian dreams.

We run our studio a short walk from the end of the transcontinental railroad. This was, at one point, the terminus of the North American colonial experiment. The old station is no longer even connected to the train lines, and instead, the place is hitched, ever westward, to a global port of Pacific trade. End of the line for "manifest destiny."

End of the line for "manifest destiny."

Some aspects of these urban environments can seem dystopian. These communities have been hit hard over and over and over. From the urban renewal that decimated thriving Black communities in the United States to the modern housing crisis, many of our neighbors are treated as externalities of a late capitalist utopia predicated on consolidating wealth for a privileged few.

From urban renewal to abandoned communes to a persistence of cults promising transcendence and self-improvement, there are so many utopias gone weird in California that there's an entire genre of dystopian fiction centered on this place—from Philip K. Dick to Octavia Butler. To live amid these extremes, we often summon the notion of "staying with the trouble," coined by long-term California resident Donna Haraway to describe ways to be with what is, rather than fantasizing about what could be.

What happens when the literary and mythic imaginations collide with reality? If you drive through California's Central Valley, you'll encounter monocropped agriculture, channelized aqueducts, and desertified landscapes. These are lands that evolved in big, wide, multi-year cycles of fire and water. They were put into intensive production by European settlers. Now the land blazes and then floods, its stabilizing ecologies diminished.

Rivers are broken. Wells are drawn down to the bones of the Earth. In places, the land has subsided dramatically because of water extraction. Water is packed into alfalfa and pistachio. Water is engineered away to growing cities. There are ghosts of rivers, ghosts of lakes. People now often attribute these changes to climate change. But all of this is far more than just fossil fuel emissions—and also different.

It's the subjugation of the land. It is hotter because the soils are bare. It is drier because the old-growth forests have been cut and are now grasslands, and they no longer co-generate the cooling rains. In the winters, huge atmospheric rivers from the Pacific still crash into the Sierra Mountains and build up the snowpack. If you go east and over the high Sierra mountain passes, you drop into an enormous valley in rain shadow.

Payahǖǖnadǖ means the land of flowing waters in the local Paiute language, sometimes called the Owens Valley. It sits leeward of the Sierra mountains. It would be dry, but for the spring meltwater that fills the valley. This is some of the most pristine water in the West. A century ago, the valley was taken to build an aqueduct, drawing waters from Payahǖǖnadǖ to 400km south to Los Angeles.

Los Angeles is literally fed by the waters of Payahǖǖnadǖ.

Los Angeles is literally fed by the waters of Payahǖǖnadǖ. A vast, bare lakebed blows dust through the valley. It's a powerful example of oblivion. The land of flowing waters has been drained, transformed into a manufactured desert to feed the utopia to the south.

All of which brings us downstream to where we work these days. We've been invited to work in the region by people who earnestly believe that the Los Angeles basin, ever a place of teeming life, going by many names, might heal its living ecologies and bring its modern infrastructures into accord with the cyclic forces of water and relationship, and supporting its peoples to participate in this change. The basin has been a place of holding and catchment, concentrating life of all kinds, from mangrove to wetland to upland chaparral. It is alive in the cultural imaginary of humans worldwide—a generator of images and dreams.

And yet in recent times, due to intentions both good and ill, the landscapes of the basin have been simplified and desiccated. Capped in concrete. Wetlands entombed and reduced. Riparian corridors eliminated. Breaths of life and land gasping.

We believe that these may be brought back to some increased ecological function, thereby healing the lands and peoples. But to address water, water must be seen with new eyes.

To address water, water must be seen with new eyes.

Los Angeles County is a modern city-state of 10 million people, spread across 88 cities. Lands of the Tongva, Tataviam, Serrano, Kizh, and Chumash, one of the most studied and mediated and romanticized and demonized places on Earth. Los Angeles is a great industrial manufacturer of utopias. And to do this, it draws water from all across the West.

When the rains come, they speed into concrete-bellied chases. Rain pulls in sheets over roads and parking lots and thousands of acres of asphalt. It was not, is not, desert.

Visualizing a valley oak tree's evapotranspiration cycle (Spherical/Almost Human)

Our work in Los Angeles now involves using technology to visualize these flows and connections, working with communities to imagine how they might transform. And this is practical business. The county of Los Angeles is now taxing impervious surfaces anywhere where the land is sealed in concrete and where water can't be absorbed. Hundreds of square kilometers of asphalt now equal hundreds of millions of dollars every year committed for distributed community-based water infrastructure. This process almost always involves capturing and holding rainwater in the land. Whether underground, in catchments, or in living things such as trees and soils. It always involves humans who plant, water, maintain and tend, rehydrating landscapes, recreating habitats, wherever space might be found. They, and we, are working at the level of the microclimate.

So just a reminder, the Earth has heated by nearly a degree and a half centigrade, and to cool the Earth by that same amount—the whole planet—will probably take centuries—if we can do it. But there are places in Los Angeles—and really any big city—where you can see changes in heat of 10, sometimes 20 degrees.

So we ask how, in places like this, might we act in accordance with the laws of the living world?

So to cool a neighborhood by that same amount, by a degree and a half, or 2 or 3, really can be done in a few years. So we ask how, in places like this, might we act in accordance with the laws of the living world? What is the potential for healing? How can community members advocate and build power collectively?

It's 1,000,000:1 odds, but what else is there to do?

We might call this climate adaptation or resilience planning or community co-design, but we think of it as living infrastructure. In cities, much of the work of now is cooling and stabilizing at ground level. At best, we will laboriously undo a century of over-construction, over-paving, over-heating. Trees planted must be grown and watered. Communities must be grown and watered.

Is it possible to counter an expired utopia with a new one?

V. Denouement

Von Karman vortices, swirling clouds that appeared over the eastern Pacific Ocean on April 30, 2024 (Image via CIRA)

Instead of inhabiting "no place," what if true utopias are deeply embedded in places? Instead of embodying ideal abstractions, what if they reveal deep relations? In the realm of complex systems, chaos often reigns supreme. Within turbulence, order emerges. This is what physicist Ilya Prigogine calls "islands of coherence." Prigogine won the Nobel Prize for developing mathematical models of chemical oscillators that visualized how these form in emergent order.

You're seeing some here. In other words, pockets of stability form spontaneously, even in the most chaotic environments. And as islands emerge from chaos, these small, coherent structures have the potential to influence and transform the entire system, driving systemic change. Let me repeat: when elements within a system align coherently, they can spark wider transformations. In the 1960s, around the time of Expo 67, Western scientists began realizing that our spherical Earth itself is a true island of coherence.

It was an era when new myths of outer space were emerging through 20th-century science fiction. However, visions of the future took a dystopian turn, reflecting the mood and fears of the Cold War. But when photographs of Earth from space were sent back from satellites and astronauts, they transformed perceptions of our home planet. The ancient dream of a god's eye view from outside had finally become a reality.

And for many, these images revealed the interconnectedness of what, from afar, seemed like a planetary utopia, erasing the imaginary political boundaries that were carving up the world. Concurrently, there was a scientist named James Lovelock who started studying satellite imagery of Mars. And he made an unexpected discovery. Its atmosphere was in a state of maximum entropy, suggesting that it was completely devoid of life.

Earth: Our Living Planet by NASA Scientific Visualization Studio (2017)

This stood in stark contrast to Earth's atmosphere, which exists in a dynamic state of self-regulation. This led Lovelock and his colleague, microbiologist Lynn Margulis, to formulate the Gaia Hypothesis, the theory that, in effect, the Earth—as a system—is alive. This was arguably the most unexpected and important discovery of the Space Age. Seasonal cycles of countless lifeforms breathe together, evolving with the land, air, and water that continuously regenerate an atmosphere conducive to life.

Gaia contains multitudes, a nested web of complexity beyond our full comprehension.

Gaia contains multitudes, a nested web of complexity beyond our full comprehension. And this is the crucial existential point that most techno-utopians tragically overlook. Life, and especially complex life, thrives through this intricate web of reciprocal relationships.

A few years ago, the boundary between the literary and the literal of utopias began to blur for our studio. When California author Kim Stanley Robinson published his acclaimed climate fiction novel The Ministry for the Future, many readers were captivated by a chapter detailing dozens of utopian ecological projects that, taken together, represented a distributed ministry of planetary care.

As he was writing the book, his consulting ecologist reached out to us, and we sent along a map of over 350 regenerative project documentaries that we've been curating for a number of years, with each project kind of exploring their locally unique ways of healing land, holding water, and governing in community. We were delighted to find these projects included in this poignant chapter of Robinson's book, drawn alphabetically from our map.

But he doesn't reveal that the entire chapter describes actual projects that have already been brought to fruition. It was a peculiar inversion. Instead of dreaming of distant utopias, Robinson presented these real contemporary micro-utopias as future fictions. Each of these projects is deeply tangible. Each is built around the regeneration of will, of life, of care. And for us, these are the only utopias worth pursuing.

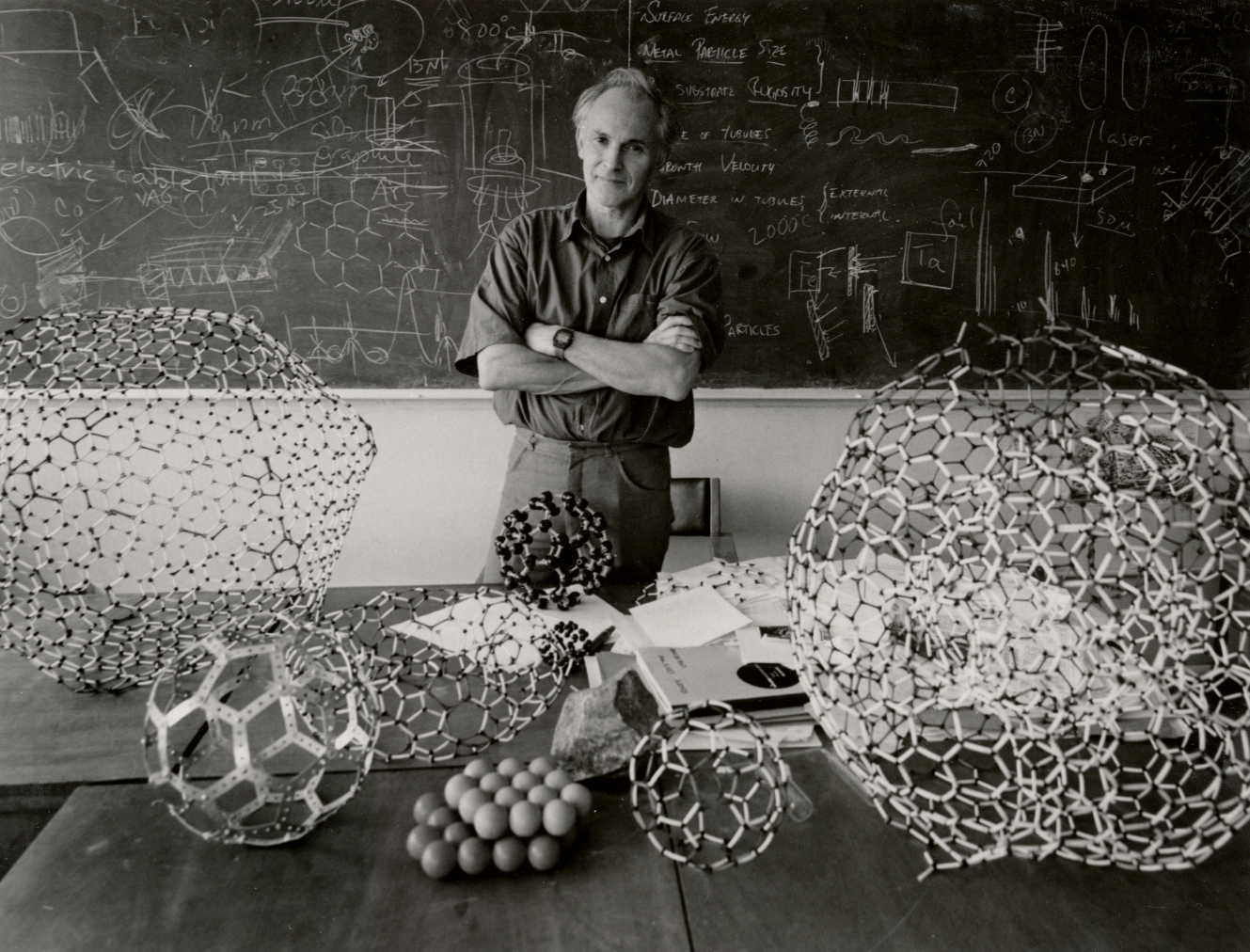

Which brings us back to Montréal and its Expo 67 dome, this iconic structure. During the fair, the structure's elegant, ephemeral space left an indelible impression on countless visitors. Among them was Harry Kroto, a chemist who would later win the Nobel Prize. He credits his visit to the U.S. pavilion with inspiring the discovery of a third form of carbon.

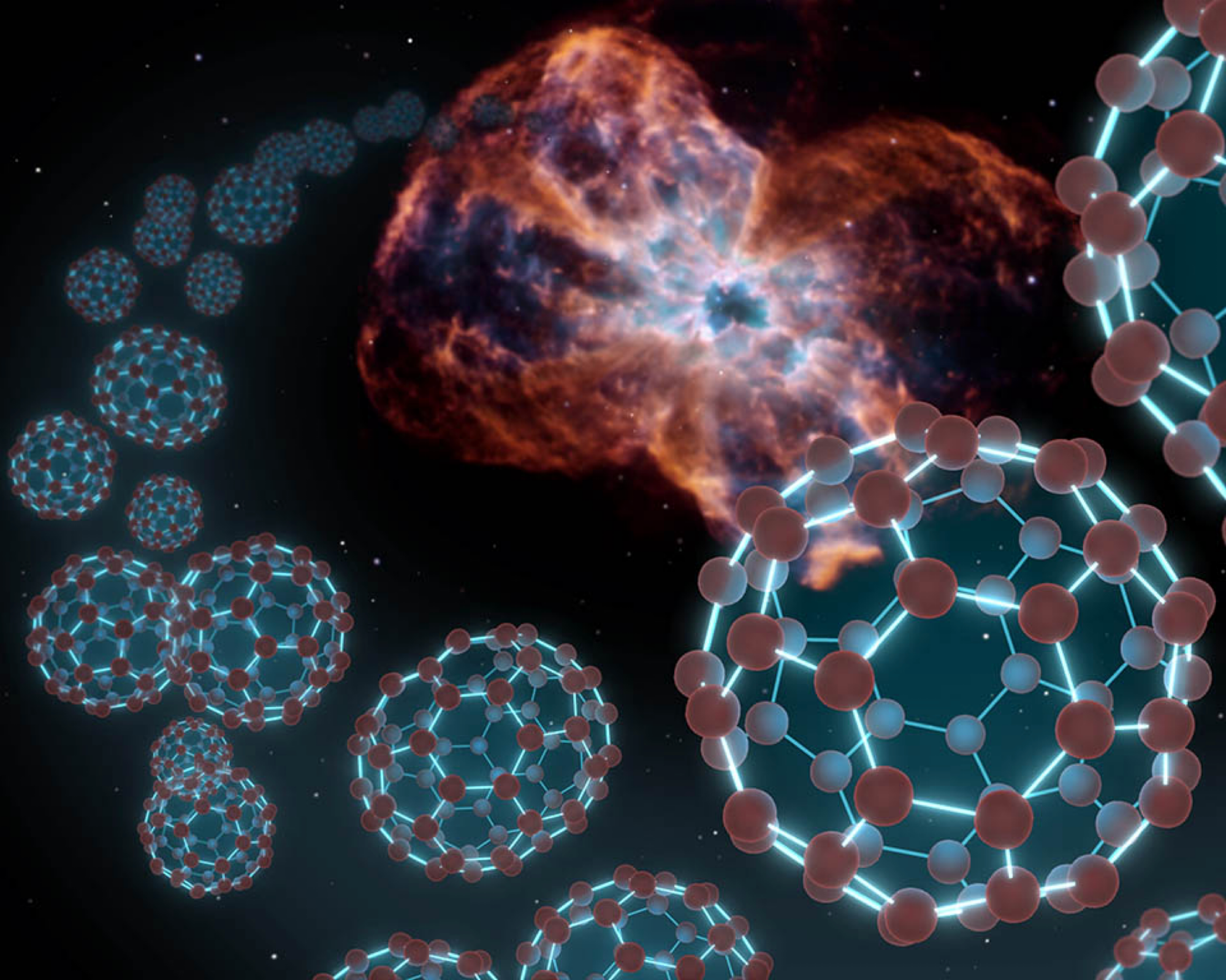

He remembered the structure, and it helped him to identify the structure of this molecule. It was called carbon 60, which he ended up naming the buckminsterfullerene. And this molecule is the strongest ever discovered. Its geodesic structure is unique: the larger it grows, the stronger it becomes. Buckminsterfullerenes are also the largest molecules ever observed in space, discovered flowing from the remnants of celestial supernovas when stars explode.

When it comes to utopias, sometimes the side effect is the main effect.

Kroto speculated that this carbon molecule may have seeded the conditions for life on Earth. So even though Fuller's vision for the dome was never fully realized—and it eventually burned—it had an unexpected, enduring impact beyond the fleeting utopia of Expo 67. When it comes to utopias, sometimes the side effect is the main effect. It's not about the dome.

All utopias are fleeting. Yet they can cast long shadows through time.

Instead of escaping to utopian fantasies of conquest, Fuller's utopia invited a reimagined relationship with technology in service of life itself. He called on humanity to prioritize caretaking and stewardship over profit and ownership—to remember that Universe does not belong to us, but that we belong to Universe.

Further Reading

- Utopia or Oblivion: The Prospects for Humanity by R. Buckminster Fuller

- Utopian Legacies: A History of Conquest and Oppression in the Western World by John Mohawk

- Utopianism: A Very Short Introduction by Lyman Tower Sargent

- Design for Micro-Utopias: Making the Unthinkable Possible by John Wood

- From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism by Fred Turner

- Astrotopia: The Dangerous Religion of the Corporate Space Race by Mary-Jane Rubenstein

- American Dreamer: Bucky Fuller and the Sacred Geometry of Nature by Scott Eastham

- Gaian Systems: Lynn Margulis, Neocybernetics, and the End of the Anthropocene by Bruce Clarke

Credits

This was a keynote for the iX SYMPOSIUM / MUTEK Forum in the Société des arts technologiques' Satosphere.

Sound Design: lissom (Tana Helean)

Additional Visual Production: Brian Ziffer, Michelle Grenier, John Pavlus, Almost Human Media

Compositing and modeling: Yan Breuleux

TouchDesigner virtual environment: Rémi Lapierre

Convened by Luc Courchesne

Partners: Société des arts technologiques, MUTEK Forum, Fond des Médias du Canada, SYNTHÈSE, L'École NAD-UQAC, Hexagram

Special thanks: Allegra Fuller Snyder, Monique Savoie, Kurt Przybilla, Elizabeth Thompson, Bonnie Devarco, Jonathan Lapalme, Patrick Dubé, Marcel Côté, the Spherical crew, Accelerate Resilience L.A., RIVER Collective, Owens Valley Indian Water Commission, Walking Water, and the Mokelumne River watershed

Performed in Tiohtià:ke/Montréal, the unceded Indigenous lands of the Kanien’kehá:ka/Mohawk Nation