Tending to the life web

A remembrance for Newton Harrison

Originally written for and performed at Newton Harrison's memorial on November 6, 2022 at the UC Santa Cruz Arboretum and later published in Leonardo Journal's special section Disremembering the Harrisons.

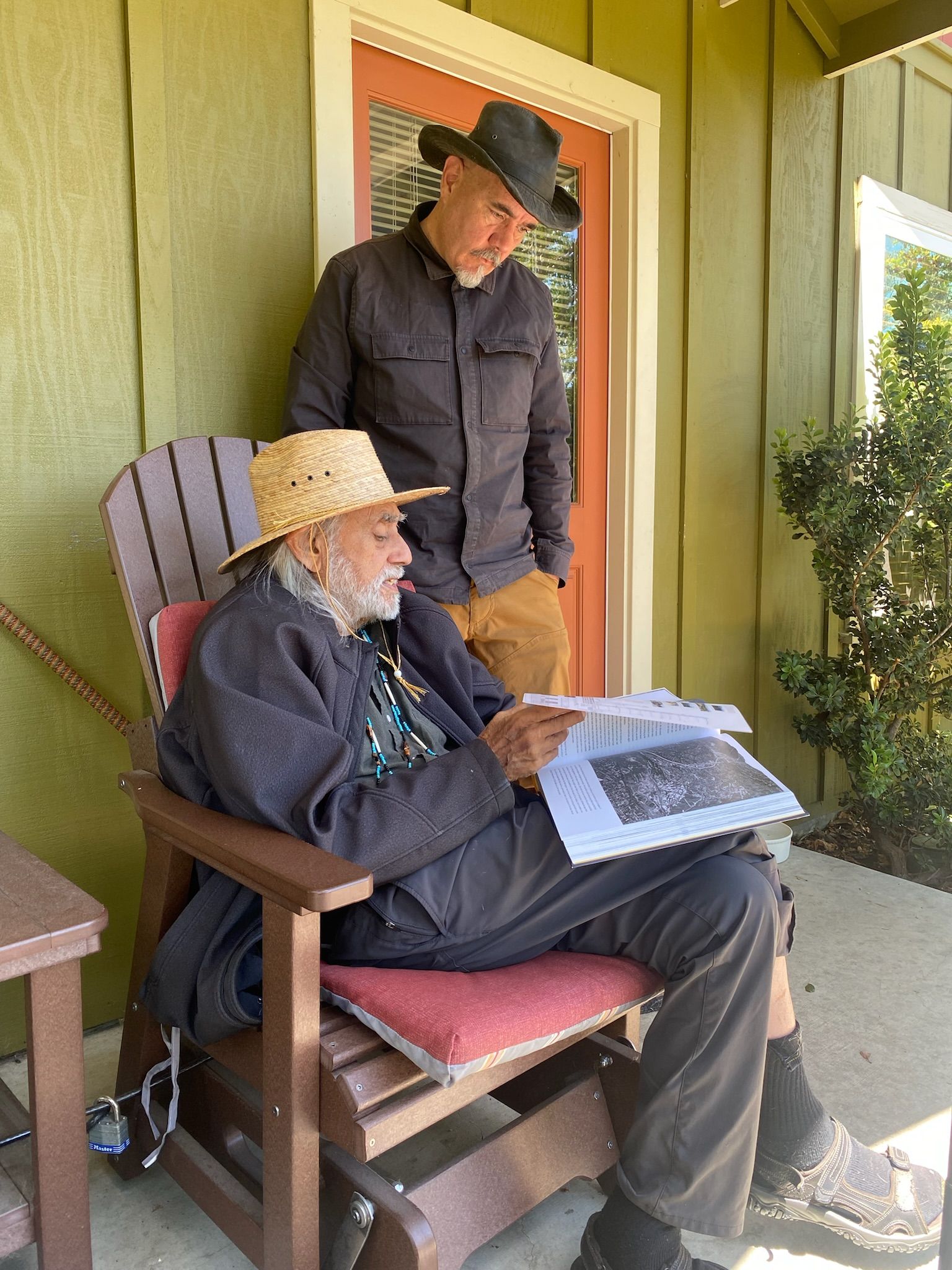

The last time we saw Newton he was sitting in the sun on his front porch in Santa Cruz, facing East. He was lean. His hair was long and elegantly combed back. The small wildflower meadow that he and Helen, his late wife and collaborator of five decades, had transformed from a lawn was blooming with lanky yarrow. We talked for a couple of hours while our dog heated herself on the sun-warmed stones.

As usual, it took us no time to get into it. Newton could be impatient with pleasantries, at least with us, and was always ready to turn our focus to the studio’s latest work. A reimagining of the Siberian steppe. A voice of the world oceans. A new water commons for Scotland. All visions of grand potential, of healing, at a scale that few artists dared to touch.

Helen and Newton Harrison’s works were defined by poetics. Their language was plainspoken and unburdened. Every statement rang as a prima facie description (as he liked to say), illuminating places with maps and words and a clear line of potential transformation.

“If we don’t tend to the life web,” Newton told us that day, “we don’t have free will.”

Talking to him like this could be quietly devastating. Sitting on his porch we’d find ourselves tapped into the unsentimental slipstream of a planetologist. He would casually remind us that almost nothing currently being done by humanity involves long-term consideration of the integrity of the life web. He called the resultant ecological shocks the force majeure, which he saw as the primary counterforce to the destruction caused by anthropocentric hubris. His research and artmaking were meant to help our species anticipate and adapt to rapidly changing environments. He was always happy to let us know that whatever we were working on was incommensurate with the scale of collapse caused by the accelerating simplification of Earth’s living systems.

Yet Newton's deeply held ambivalence and cautionary tales were always strangely enlivening. He didn't exclude himself from his critiques. He had long since accepted the paradox at the heart of his work: pursuing visions of impossible possibilities. He preferred the trickster's million-to-one odds, setting the bar so high that he could never become complacent or self-satisfied. As a result, his parables and anecdotes became cross-generational transmissions, distilled from his lifetime of astute observations and creative experiments.

Of course, it was really two lifetimes in one. The Harrisons’ work was a unique expression of their close collaboration. They often spoke in the plural voice. Over their fifty-year creative partnership, they cultivated the ability to think like one another, and to do each other’s work with one mind. Their collaboration embodied the symbiotic entanglements that were at the very heart of their studio, and the Center for the Study of the Force Majeure.

After Helen passed in 2018, Newton carried their work forward. He told us the worst thing for ecology has been the oppression of female intelligence. He praised Helen's gift of generating a field of trust that was essential to their work. And he attributed their successes to this integration of the masculine and feminine, human and non-human, social and ecological:

"We set out to be unafraid of complexity. I say every living thing is my companion."

Shortly before the first COVID lockdown, Newton visited a collaborative exhibit we curated at the Gray Area in San Francisco. Much to our delight, he was enthusiastic about the ecologically themed works, while also insisting that he was probably the most intolerant person we’d ever meet. He had little patience for what he called “gestural” works that pointed to ideas about ecology rather than actually enacting process of healing and transformation. He also admonished us:

"If I have a critique of all art shows, not just this one, it's that we haven't yet found the way to jump out of the gallery and into the real world. Helen and I actually have done this, and we're successful at it. But we have to say that out of 50 years work, four pieces are successful at it."

Newton was undaunted by failures, believing that artists had a responsibility to glean learnings from iterative practive. He and Helen approached their work with the discipline of scientists and engineers, as evidenced by numerous unique discoveries and outcomes. He referred to their method as preemptive planning, fully anticipating that their hybrid, whole systems investigations would become increasingly valuable as ecological breakdown progressed. He was characteristically unambiguous about why he’d chosen art as his preferred research method. When asked why he was an artist rather than a public planner or other profession, he forcefully responded,

"If I am any of those things, other people control my agenda. If I'm an artist, I make the agenda. Or Helen and I when we were working together. And therefore it's entirely different from being in a field that has rules. I make my own. And you can see it, piece by piece. That's why it's okay to be poor. Where's your payoff? The payoff is you're a free agent. On top of that, you're paid to do what nature does. Everything in life improvises its existence. So do we artists."

Sitting with Newton on that summer day, we were reminded of how bitter the gift of knowing a truly free agent can be. A few months prior he’d received a cancer diagnosis, which he’d accepted with equanimity. He spoke about how to contend with existential realities with a bluntness that was rare, even for him. As we discussed the cascading effects of climate destabilization, we asked what he thought was the best humanity could hope for. Without hesitation, he answered,

"As the life web shuts down, that catastrophes interact in such a way that they force change."

The change he envisioned was grounded in deepened relationships with places and attunement to changing ecological dynamics. Imagining post-collapse scenarios, we discussed the necessary re-emergence of bioregional governance systems, the re-localization of food systems, and the redirection of education towards capacities for survival. After half a century of experimenting with aesthetic and poetic enchantments, he’d concluded that the imminent threat of death was the ultimate teacher:

"It turns out that no matter what you say to anybody, they ain’t going to change but for their own lives being threatened."

Speaking on behalf of the life web, he proclaimed:

"So let’s threaten!"

Newton Harrison at his home studio in Santa Cruz, CA, July 2022. Photos by Dawn Danby and David McConville.

David McConville and Dawn Danby are the co-founders of Spherical. David is a board member and senior researcher at the Center of the Study of the Force Majeure, founded by Helen and Newton Harrison.