Invocation for Spaceship Earth

The way we cooperate will be the way we survive

From our vantage point here, it can feel like we dodged some bullets. Not entirely, not ever entirely: many of the slow-motion tragedies we were living and witnessing indeed unfolded, and ahead of schedule. Peatlands off-gassed. People died by the thousands of thousands. The thermometer crept steadily upwards.

And, of course, not everything happened as anticipated. We probably could've anticipated that. Our victory was to head off a particular kind of annihilation, and keep the spaceship operating on its perfect course through the void.

For some years, around the world, groups of humans had been developing tools and techniques for effecting change. They gathered together, they monologued. They covered walls with looping notes and tiny multicoloured papers. They wrote reports. They ran some experiments. They collected their insights and shared them with anyone who could punch in a search query.

The best things that happened were that they found out ways to work together, dream together, and agree on a set of specific, tactical goals. This wasn't ideal but it was better than the handwaving and handwringing that preceded it.

The goals were often misunderstood. By the time they were fixed, a lot of other things were fixed, too. The acute angle of the parts per million had long since been locked in. Diatom-sized polymers absorbed into tides and bloodstreams. The bees and frogs weren't having it.

Through all our deliberations, the spaceship kept on sending us signals. We were relatively stupid so we initially failed to read them. The spaceship was letting us know that we couldn't ever just do one thing: we couldn't adjust the thermostat without the trees, and couldn't do that without the soils. The emissions wouldn't abate if we couldn't bring back the rains.

In fairness, many of us had forgotten how to read the signals using our innate senses: our ears and eyes and experiences and histories and the deep memories of our cultures and places. We'd put all of our stock into our industrial sensing machines, and they, too, were relatively stupid to start out.

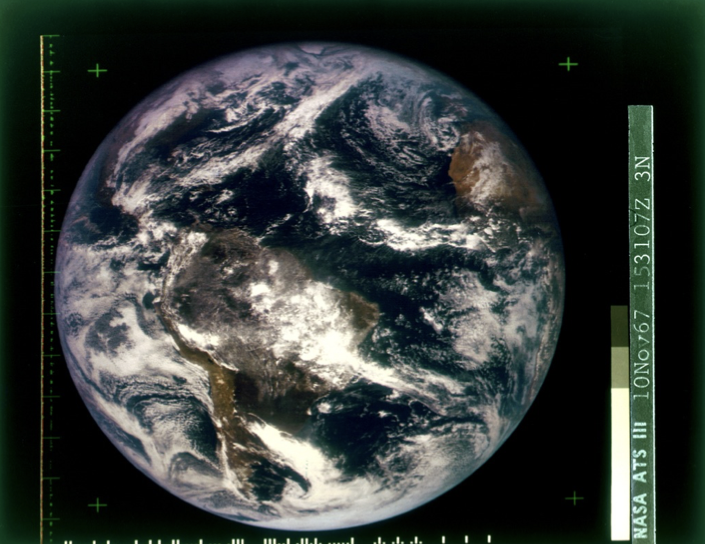

At a certain point this started to change. The humans started to get a clearer picture of the spaceship, a literal picture, and over the years it came into sharper and clearer realtime view.

In these images and datasets, brought forth by the surge of new technology and sensemaking, we could pick up more messages. The spaceship allowed us to observe that while the worst of things couldn't be seen simplistically, neither could the best of things. The spaceship didn't run in the way we had thought. The swirl of complexity meant that we needed to think together in different ways. How to do this? It was confounding.

Many societies had positioned their humans as mechanic gods, skilled at dominion and power. Some of the humans very much liked to think of themselves that way. Setting down their godship was something they resisted. Most of the technologies developed during those years were made by people who were blind to the spaceship they inhabited. The technologies were used to fragment and dominate.

In 2018, a small crew of humans found themselves as caretakers of an ancestor's legacy. The ancestor, who had died decades before, had been a man with uncanny, tragic prescience. He picked up signals from the spaceship, patterns that he saw within and beyond it. He wrote these observations down in multisyllabic poems stacked deep with intentions and imagery. It wasn't for everyone, this stuff.

Looking back at the work written by the dead ancestor, the crew found curious descriptions of the time they were in. They also found indications that the technologies the ancestor had foreseen had also come into being. The spaceship was ailing, but the ways of understanding it were exploding.

The crew examined the work done by others, all the gatherings and reports, all the datawrangling, and they tried to figure out what was missing. They picked up where the others had left off. They gathered their community. They believed that seeing and understanding the spaceship was the most important thing. If the crew couldn't understand the ship, they couldn't adjust its course.

There had been a belief that simply knowing the spaceship's problems would be enough to get humanity to fix them. There had been another belief that having all the data would change everything. These ideas weren't false, but they felt incomplete. What was different in the ancestor's time? What was true now?

Urgency. That seemed to be the first thing. The ancestor lived and wrote at a time when it was easier to distance oneself from the effects of chewing up the commons. By 2018 there was nowhere to escape to, no remaining illusion of escape. The refugees were already on the move.

And the tools and knowledge for maintaining the spaceship: that seemed to be the other thing. Humans had indeed figured out how to collaborate with each other, with the machine intelligences they devised, and with the patterns and flows of the spaceship itself.

Instead of mechanic gods, the humans became transceivers of knowledge, and tenders of the spaceship's living systems.

How is it, to be a forest? A forest does its foresting, and foresting is a conversation. Just like we're talking here, using atoms and energy to share information.

Messages pulse through mycelia. Nutrient gets passed around. Perhaps you like to think of it as a machine? It isn't one. Lucky for you. A forest doesn't stop foresting when it runs out of battery life. It will stop if we dismantle it into parts. It will stop if treated like a simple woodmaking factory. If you forget that it's keeping the city's temperature cool, forget that it cleans the air, forget that it absorbs all that absorbable exhalation, forget that its bacteria draws the rains down into the soil.

The forest can do ever more foresting but the crew realized it wouldn't do it on its own, not anymore, not on their timeline. One of the curious side effects of all the digging and burning was that were so many of us here. Eight billion human mouths to feed. But also eight billion pairs of human hands.

What do you think humans do, when they're humaning? Did you think these gardens just appeared here by chance?

You are you. You are also bacteria and ocean. We are communities within communities, spontaneous cooperations all the way through.

The ship is signaling. It tells us: The way we cooperate will be the way we survive.

We need all hands on deck.

Welcome to Spaceship Earth.

Dawn Danby

April 16 2018