Invocation for N'Dakinna

On value, fiction, and mediums of exchange

Performed facing Agiocochook, under the stars

Abenaki / Abénaquis Wabanaki Territory

Dawnland Confederacy

a.k.a. Bretton Woods, New Hampshire

11 July 2018

To the South of here, on the side of Mount Sunapee, there’s a stand of trees that are 400 years old. It’s rare in a place like this one, on the Eastern Coast of North America, where the forests are so young.

They weren’t always young, of course. But after the glaciers sawed through this region what it wanted to be most of all was forest, and that’s still what the land wants. Farmland left fallow here will eventually fill back in with young trees.

If you walk through the forests here, you will come upon hand-built rock walls, where farmers cleared the lands of the glacial rock, and then abandoned it for lands further West.

Once upon a time some new people arrived here and found trees that were unimaginably tall.

Some of them recognized them as masts of ships, masts in disguise, and saw that they were clearly earmarked. They notched them deep with broad arrows, three strikes of an axe, to let others know that these trees, living and dead, every one of them belonged to a king. The king had never seen the trees himself, but he had people, and those people knew ships. Anything above twelve inches in girth, to be fallen for masts, to fight in distant wars.

The mast-cutters worked for a Crown who was using a clever new trick. The trick was an idea, that the seas belonged to no one. The land belonged to no one. If something belongs to no one, then it is there for the taking. You’d have to be a fool to leave it. By that logic. The Terra Nullius, as it was called, is the no-man’s land. The land of no men, of no women. For the taking.

When the king’s people came here they had to make up a story that the people who were here already somehow didn’t count. You see the clever trick? The people would have to be seen as something other than people.

And there were people here, of course, Abenaki people, and they were not confused about the purpose of trees. They didn’t mistake the tallest among them as ship parts or confuse them with exports. N’dakinna (or the Dawn Land) is the name of here, and its trees held relationships, were relationships: the Abenaki who lived here knew them as family members.

I was born North of here, in another country across a modern border. I’m an immigrant born of immigrants, so it’s not my place to welcome you. The best I can do is share what I’ve seen.

For two decades I’ve come here every year. The ecology is nearly the same as where I grew up. Or: it serves up a satisfying simulacrum. I can squint, and part of me knows this place. The border is a newish thing.

Each of us might imagine a different temple, built of the materials we hold closest.

You might assemble it from the sense memories of the places you know best, or where you grew up.

I build mine from the feel of pine needles on bare feet, the first hit of lake water in midsummer. Every night this week I’ve listened to the loons on the lake. They sing down a minor third. I love them: They’re spooky as hell. Their people have been here a lot longer than mine.

The biggest trees were useful for other reasons. The floorboards in my parents’ farmhouse in New Hampshire were fourteen inches wide. Panels on the walls, eighteen inches or more. It might get you killed, building from wood like that. But also admired. Flaunting the King’ Pine was edgy, unapologetic. Revolutionary, even.

Visitors from Europe had been floating the North Atlantic for centuries. Coastal people, Basque and Portuguese and Viking.

But this time, the Europeans seeded the Northeastern forests with a new, insidious version of trade, turning beavers into hats, forests into “woodlands”, ceremony into money, and turning the first peoples, already now suffering and diminished, against one another.

The English Crown was merely the most efficient at extracting distant trees to conquer the seas. Their faraway king was building an empire on which the sun never set. They declared that their liability was limited. The king needed six thousand North American trees for each of his warships. The tallest of the white pines, masts piercing the horizon line.

In 1772, there was a skirmish over those trees. Just down the road here in New Hampshire, in a place called Weare, there was a mill where the contraband boards for my parents’ farmhouse had been cut. The colonist builders rioted against the king’s men, for taking the best of the trees. A kind of taxation without representation.

The Pine Tree became a primary symbol of Colonial Resistance. They called it the Liberty Tree. They put the pine tree at the centre of their white flag, carried by George Washington, which declared their efforts as “An Appeal to Heaven”.

As one of them [Joseph Warren] wrote, “appealing to heaven for the justice of our cause, we determine to die or be free”.

First they fought over the Pines, and soon, they fought over the Tea.

Well before the Europeans arrived, the Abenaki people who lived in the shadow of this mountain were part of a vast network of confederacies, tribes and communities who had lived in the forestlands for millennia.

Not to idealize things. They were sophisticated humans, diverse and complex, cruel and kind. And yet they cooperated with the place and with each other. They warred, and they made peace. Diplomacy with all their relations, including the land itself.

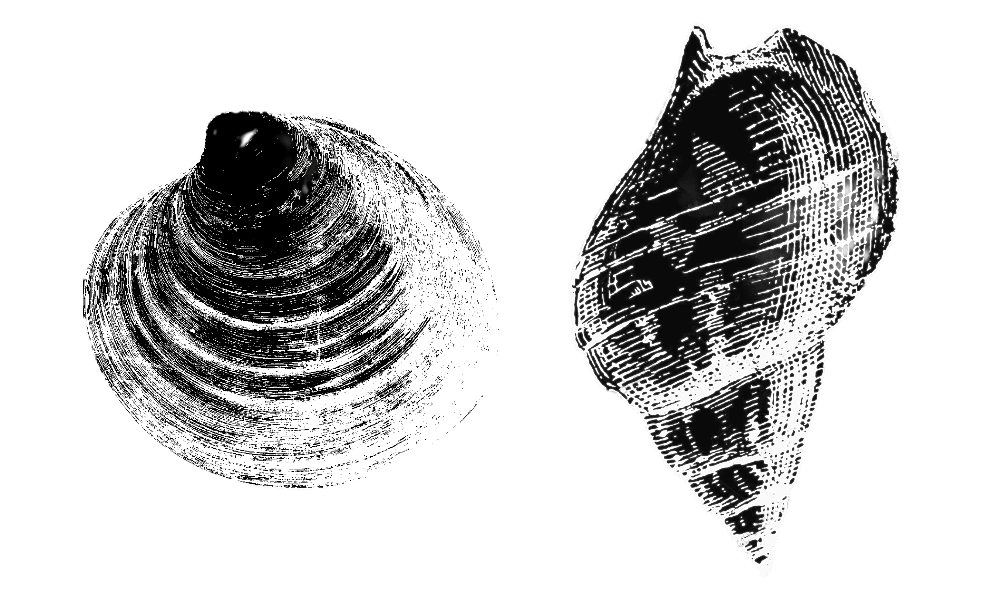

The nations extended to the Atlantic coast, and the coastal peoples collected the seashells of bivalves, quahogs and whelks. They cut these precisely into long beads, white and purple, light and dark. These beads were woven together, into patterns on belts, to tell a particular story.

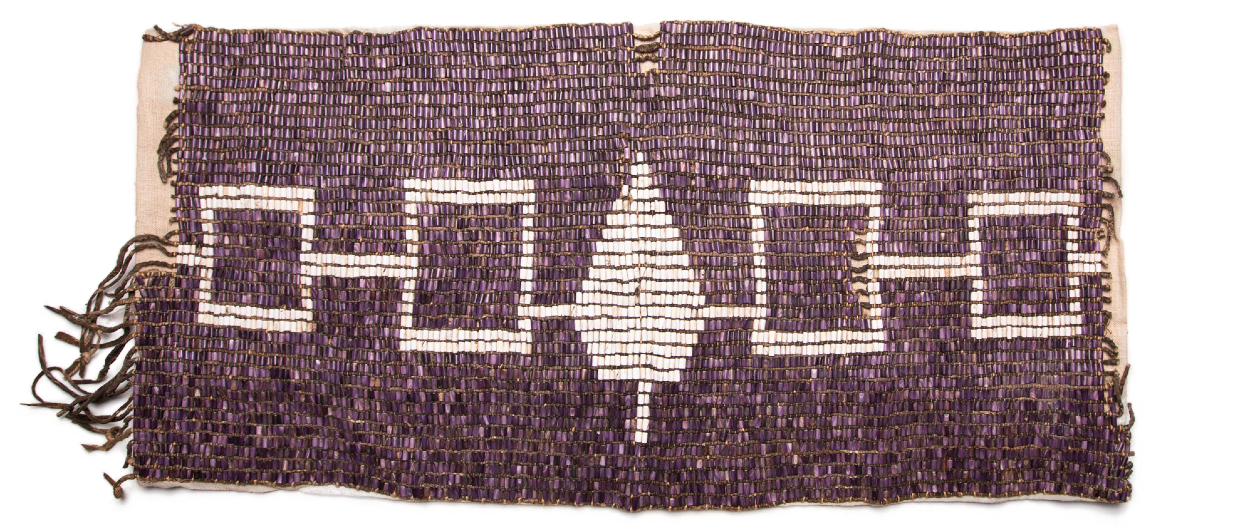

Sometimes they were taken apart, reconfigured, to tell another. The light and dark formed a kind of Binary Code with which to send a message, or represent an agreement.

At times, warring nations came together and created confederacies. The Haudenosaunee, otherwise known as the Iroquois. The Wabanaki. These confederacies were held in Peace by a deep agreement and sealed though the creation of an artifact, white and purple beads woven into bands, telling the story of the pact.

Wampum, the white and purple beads, are often called the first money of the United States. Is that what they were? Maybe. But no, not originally.

This was a currency of a different sort: It traced the flows of relationships, of social structures, of provenance. It was a record of transactions. It was a mnemonic device, enabling oral histories to distribute memories among a community. Above all it was used to arrange and rearrange relations among people.

Wampum as a medium was storied. The medium itself was divisible, reconfigurable. Sound familiar?

It was a technology of trust, but it didn’t replace the trust. It stood as a sacred record of the exchange, a ritual of a specific meeting. At the centre of the record was the story.

Seashells, gold, paper, lines of code: all of these are based on stories. Some might call them fictions. Or constructs.

Wampum’s value came through the addition of human care and creativity. In which shells, made of hard ceramic, were infused with meaning.

Ceramics are beautiful, curious materials. Humans use extreme heat to fire porcelain, kilns to make pots. But there are shelled creatures who manufacture it in cold Atlantic seawater. Their very existence reveals the health of their ocean. Ceramics in nature are the product of a healthy living system. Any of us who has grown a human within our own bodies has created the seeded conditions for tiny teeth to emerge, precisely at body temperature. These processes, I think we can agree, have an inherent value.

The original value of ceramic wampum was not in its rarity, or essential quality, like gold, but in how it maintained a sacred reciprocity among peoples. It was a covenant.

And this was how it was used, even in cooperation with the early colonists. There are wampum belts that tell the story of agreements between European settlers and the native communities who came to their aid.

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy, of the Nations to the West of here, brought five warring tribes into accord centuries before the colonists arrived. The confederacy was represented by a wampum belt that represented the connections among the five nations, with a tall pine against a dark background. This was the Tree of the Great Peace, representing the “Law of the great peace”.

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy was first placed into written form by Benjamin Franklin, one of the authors of the United States’ Declaration of Independence. In their lives, these colonists had only ever known monarchies: in the British Isles and Europe, their people had been under the thumb of hierarchies for centuries. The notions of freedom and independence from subjugation were dreams. They had never seen a participatory, non-monarchist governance functioning in a sustained way. Here was a complex civilization that didn’t distinguish between humans and the rest of the living world.

European traders co-opted wampum as their medium of exchange. Colonists were cash-poor, so wampum became their legal tender. For a brief time, wampum beads in isolation could be exchanged for shillings.

There’s no evidence that the nations used it as currency amongst themselves, however, despite how deeply they were pulled into interrelationships with the colonists. These communities existed in parallel systems of value.

Are individual beads wampum at all? Can a bird outside its habitat survive?

Predictably, the system collapsed. Europeans eventually mechanized Wampum production on the Atlantic Coast, effectively minting money, but by that time the tides had turned: minted metal coins had made their way to America, and the wampum miners took their winnings and closed up shop.

Our sense of value is cosmological. It’s based on what we believe the universe is. It has to do with how we perceive, how our cultures perceive: the trees, the seas, the useful things they offer, and whether or not we have anything to offer them in exchange.

What is it, to be connected?

It is reciprocal. Take and return. In and out, tides, breaths, seasons. The mountain here in bright summer, and in winter whipped with winds, known by the first people as the mother goddess of the storm, honored by them as the home of the gods and then named for a human man, a new American, the winner of a revolutionary war, making his appeal to heaven.

Isolation is an idea, and one rarely seen in nature.

The white pines of this region cover five hundred thousand acres. Another view: They represent 31 percent of the saw timber.

They are homes to breeding birds, to the bald eagles, and feed the rabbits and deer and everyone microscopic and huge, throughout the life web.

Right now, we are here in view of them, breathing their exhalations.

This place wants to be forest, but we know that its white pines are ailing. The springs have gotten warm here, and wet, and the fungi are operating differently in this newness.

The trees will shift, and with them the people, as they always have. What paradigm could have led us here?

What new paradigm might lead us out?